-

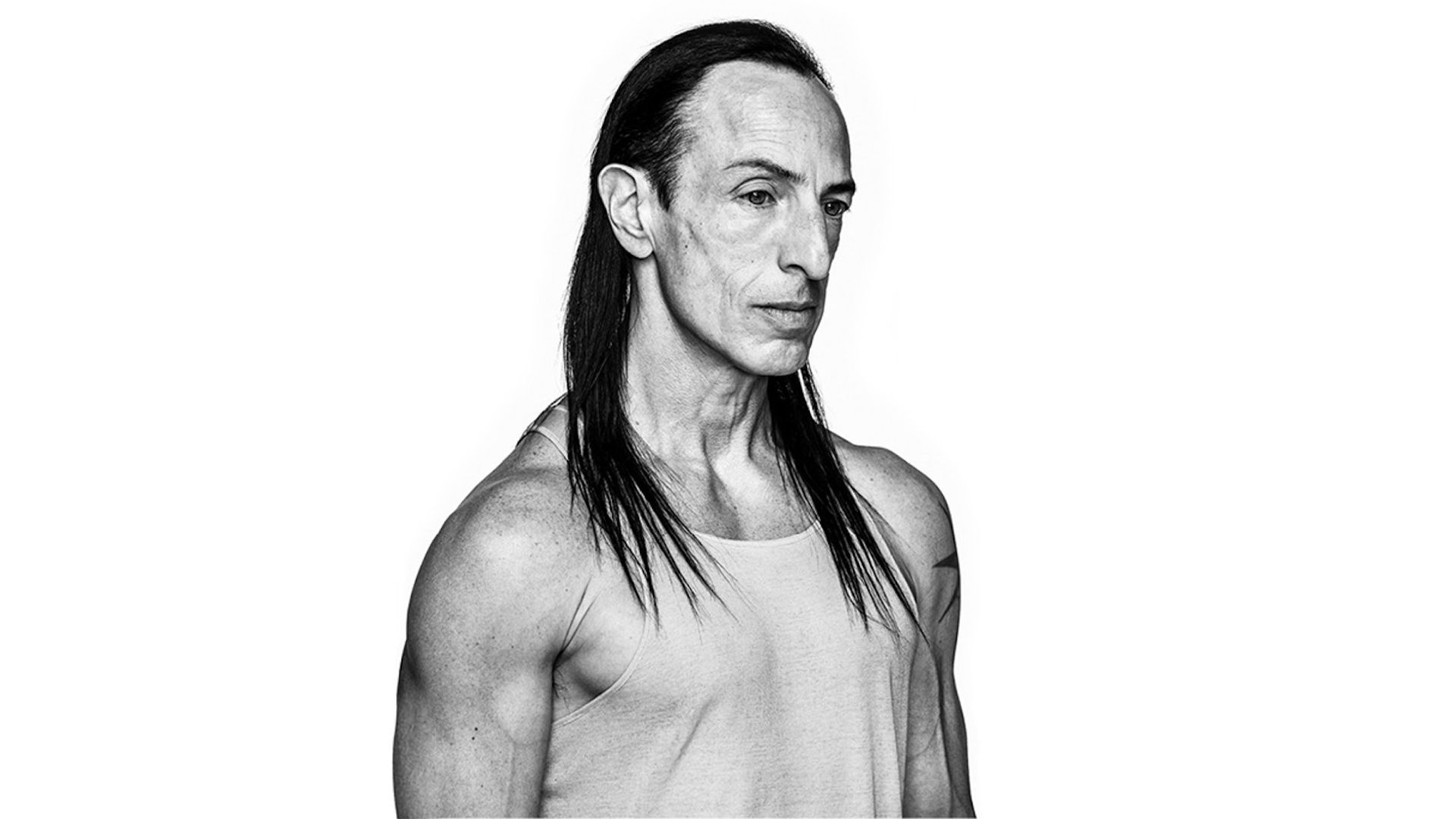

THE METAMORPHOSIS OF RICK OWENS

While the 97th edition of Pitti Uomo was in full swing in Florence, Rick Owens retired to his workshop in the small commune of Concordia sulla Secchia, around 100 miles north of the Tuscan capital, to oversee the production of his new collection. A brief respite from the urban hustle and bustle before returning to Paris—where he lives with his wife and creative collaborator Michèle Lamy—to present his new men's collection at the Palais de Tokyo. He has held several shows there previously as incarnations of his radical, candid and uncompromising vision. The designer has also used the runway to provide a sounding board for the various social messages that he wanted to convey—even if they are meant to be surprising, disturbing or shocking to the audience. He has established himself as one of the leading figures of inclusiveness by featuring step dancers (Spring-Summer 2014), celebrating strong women (Spring-Summer 2016) and the male body (Autumn-Winter 2015), as well as declaring his unease about the potential consequences of the impending environmental disaster that faces us (Autumn-Winter 2016), among others. Interview.

Printemps.com: The models that you present on the runway are often dressed like creatures from another world—as if you had summoned a sort of pagan neo-mythology—which reflects your creative influences, from Larry LeGaspi, to the Camp aesthetic, to Kabuki theatre. In your view, are fashion shows a chance to celebrate more unconventional forms of beauty?

Rick Owens: I have always reacted against very narrow beauty standards. It's even deeper than that: It's bigotry, which involves having preconceptions that we believe have to apply to everyone. Bigotry is perhaps the greatest evil in this world. And I have the chance to oppose bigotry—bigotry in beauty. Fashion shows, the way that people are judged by their appearance... if I could make all that more flexible, if I could suggest other options that aren't limited to these strict standards, it's an incredible message. We don't have to restrict ourselves to the narrow and rigid rules that exist in our contemporary culture. We can blur these boundaries and move beyond them. That starts with beauty—it's just a question of appearance, first impressions and communication—and by suggesting that all this can be more flexible, then the next step could be ideas. That can lead to more tolerance towards other people's ideas. So fashion can be spectacularly superficial—which is also fun, and I love that—but despite that, it can also have huge importance as an influencer, as a first step.

Because representation helps to shape the zeitgeist, and the values advocated by a society...

Yes, and the repercussions can be very sudden.

You seem to be attracted by extremes—the raw, visceral, pure and uncompromising. Why this intensity?

I seek authenticity, the creative gesture. I like it when people totally self-invent, when they do their best with what they have, by doing it thoughtfully. I admire that. And I love theatre. I like to be surprised, enchanted, I like when there's a dramatic act. When there's a theatrical aspect, and it isn't being saved for a special occasion, I enjoy that. When I started out [in fashion], I rejected the idea of borrowing something to present a false identity that would not be applied to the rest of one's daily life. I wanted to make everything merge together. That said, I'm not as rigid now. It was a little categorical, born from my own intolerance, and I stopped thinking like that over time. But I always defend the idea of integrating this theatrical dimension into everyday life; it shouldn't have a separation or distinction. People should be able to hold on to what they want to be, because if it's not hypocritical and it's a conscious choice, then it's authentic. With practice, artifice can become reality.

Photos: Rick Owens fashion shows. From left to right: Menswear Autumn-Winter 2020, Menswear Autumn-Winter 2016, Womenswear Spring-Summer 2016, Womenswear Spring-Summer 2020

In a way, your shows are the incarnation of a dialogue between the chaos of instinct—primary impulses—and the attempt to control them through rituals, order and structure. A discourse giving birth to the raw elegance that extends throughout your collections...

I've spoken a lot about this balance between control and abandon. Because abandon is something that has always attracted me; I did let myself go to some extent, then I got over it, and then I went in the opposite direction. But in both cases they are irrepressible and primal needs that are authentic. The slightly extreme aspect of my inspiration and my experiments concerning control and abandon, undoubtedly comes from the fact that I went as far as possible in both directions. Today I'm very much in control, but will I relapse again? I don't know.

How do you look back at your years as a young adult, when you went out a lot and went wild in Los Angeles—a period that you now associate with a sort of "abandon"? Do you view these actions as mistakes, or rather a necessary step that allowed you to be where you are today?

It wasn't a mistake at all. If I had children, I would definitely be terrified at the idea of what could happen if they followed that path. But I have a very strong affection for that time in my life. I completely transformed myself afterwards, thanks to my own determination. With a little discipline, anyone can change completely.

"I SEEK AUTHENTICITY, THE CREATIVE GESTURE. I LIKE IT WHEN PEOPLE TOTALLY SELF-INVENT, WHEN THEY DO THEIR BEST WITH WHAT THEY HAVE, BY DOING IT THOUGHTFULLY. I ADMIRE THAT."

So far, you have developed a 360-degree creative universe that is not only limited to clothing collections and fashion shows. You also offer an interior design line, books (with two published by Rizzoli last September), and different events—like the performances that you organised at the Pompidou Centre recently. Why did you want to expand your range so widely?

I think I wanted to create a protective bubble around myself. It's also a question of ego. With any designer, there's a huge display of egocentrism: It's all about being recognised and leaving a mark. Everyone wants attention, to be validated. I am both proud of and embarrassed by that. There's a tremendous need to express yourself, you have to show off so people take notice, particularly at the start, when you're still creating your identity. It's an overwhelming desire but it's also a display of ego, an embarrassing need. Who am I to think that my expression is so important that I go and knock on people's doors so that they acknowledge it? It's a bit crazy when you think about it.

Showing off your own identity as a creative is a conduit that you seem to continue to follow. Even with the clothes that you wear—you like dressing in the same pieces for several years, before switching up your "uniform" with a new variation.

Yes, because I appreciate repetition, and I like it when someone says something that they really mean. When I see someone wearing the same clothes, it tells me that they know who they are. I also like the fact that it involves a balance between extravagance and modesty, in the sense that it's extravagant to collect 50 copies of the same thing, but there's a form of modesty in sticking to it. It's like a Donald Judd exhibition. It's repetition, repetition, repetition—until it becomes super compelling.

Photo: Rick Owens event at the Pompidou Centre. ⒸOWENSCORP.

On that subject, you had a lot of reservations before presenting your first show in 2002 (you were 40 at the time), because you were worried that the fashion world would judge you for not making enough new pieces. In hindsight, do you now think that going at your own pace was the key to your success?

Yes, absolutely. My first show was probably my biggest test. To a certain extent, there was a point where people decided to put up with my pace and accept who I am. The fashion industry can seem a little hysterical sometimes, and I love being the discreet guy who is moving at his own speed on the side-lines.

You were the curator of your own retrospective exhibition "Subhuman, Inhuman, Superhuman," held in Milan in 2017. Why was it important for you to look back over your own work and edit it?

I think it would be important for anybody to have this opportunity. At the heart of it, it's about writing your own obituary. That sounds dramatic, and it is. You have the power to set the standard in showing who you want to be. Any retrospective or exhibition that's directed by someone else would be an interpretation; it's not the original, authentic voice. I could get rid of anything I wanted to get rid of, and manipulate everything. It's incredibly gratifying to be able to determine how you will be remembered forever. It's a blessing.

The exhibition featured clothes that you had created, and also some furniture pieces from your interior design range, which you develop with your partner Michèle Lamy. Why did you launch this new venture alongside your fashion collections?

That was also a question of ego. I wanted to control everything around me. I wanted to furnish my own bubble. Everyone customises their own lives, I just went a bit further—I've been a bit more obsessive.

Photo: Michèle Lamy. ©OWENSCORP.

You once said that in your twilight years, you'd like to end up in a garden where you spend your days reading and playing with kittens. Despite this confession, it would not be surprising if you actually carried on designing collections, as other designers have done before you. Do you really think that you'll retire one day?

I bet that one day my relevance will diminish, and I will have to accept that. I think it's inevitable, and I've seen it happen—I've seen the relevance of creative people fade. What should I do next? I dread that time in a way, because it doesn't seem pleasant. But everyone must prepare for some form of decline—being taken by surprise seems really stupid. Of course I would love to stay relevant until I die, but if that doesn't happen, spending my days in a garden surrounded by kittens seems like a good option.

You've said several times in previous interviews that one of your aims in life is to reach some form of serenity. Do you feel like you've achieved that, or does it feel like it's going to be a constant "work in progress"?

I think I've managed it occasionally, and I'm so determined to make it happen that it will happen—even if feeling some minimal anxiety is unavoidable. But for me, the true key to happiness is gratitude. Because there are so many things that could be worse, when you look around. And the other key to happiness is remembering that it's not a right. We aren't entitled to anything. We are lucky for all that life gives us, and when you understand that, everything becomes a lot simpler. You have to work to get anything, and we are lucky we've got what we have, whatever it is. It really helps to be serene.